Tag: Social Media

-

The Beatles never look up

What if the four distracted Beatles never looked up during the Abbey Road album shoot? This cartoon presents a funny, modern-day interpretation of the iconic The Beatles Abbey Road album cover. The only thing missing, besides Paul McCartney’s shoes, is the Abbey Road zebra-crossing. Chances are the driver also works for Uber.

-

“Build it and they will come” only works in the movies.

“Build it and they will come” only works in the movies. Social Media is “build it, nurture it, engage them, and they may come and stay.” Seth Godin

-

The great escape

Peeking at life, three inches from the screen. It’s the possibility that it may show us something captivating that keeps our eyeballs alive. Even with robotic intervention, we’re glued to that rectangular glow. There’s enough variety in the repetition to keep us hooked. But what happens when we willfully want to get away? We struggle…

-

Coping with ‘the colossal volume of memories’

In an interview with the Financial Times, Apple lead designer office Jony Ive points to one of the technological conundrums of our time: balancing ease with excess. “We have such a high-quality camera with us all the time. But it becomes irrelevant if you can’t actually enjoy the photographs you’ve taken. Even 30 years ago…

-

A little bit louder now

Provocation is neither about engagement nor expression — it’s about likes and shares. The lightning rod on Twitter will always outshine the passive inspirer, hiding from the market. But it is the quality of interactions that deliver the message. Neither the loud nor the faint succeeds. Speak softly and carry a big stick.

-

Hobbying for hobbies sake

Whether it’s trying surfing or playing the guitar when’s the last time you did something out of pure joy? In this Instagram-edited era where everyone gets their own stage, people only like to do things they’re good at. The thought goes: ‘if I can’t share it and show my best self, why do it?’ The…

-

Hashtag heaven

Luxury today and tomorrow will be defined by the ability to disconnect, to live a secret life where there’s no need to stay constantly connected for the sole purpose of a future job or fear of missing out. Social media is a poor insurance policy. Except disconnecting is not the goal — moderation is. An…

-

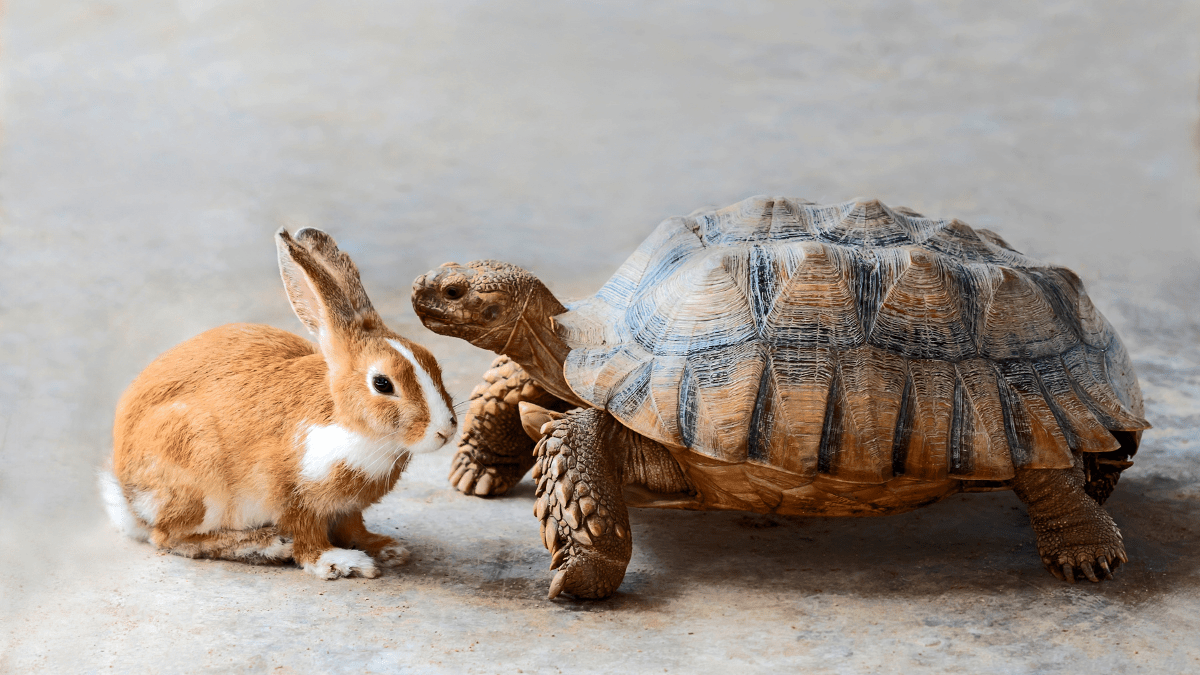

Slow appeal 🐢

Conventional wisdom says that we should emphasize speed over power. After all, he who runs the fastest wins the race. But life is a marathon, not a sprint. Malcolm Gladwell once said proper books should take at least two years to write. “We need to be a little bit more tortoise-y and a little less…

-

The sharing virus

The biggest threat to a virus is its own exhaustion. It wants to be said, repeated, and spread until it cements into a meme. Words, ideas, and apps are all types of viruses. Pretty much anything that spreads. Most are benign of course but perhaps none is more pervasive and self-inflicted than the sickness of…

-

From bytes to bits of reality

We demand privacy yet admit ourselves to the culture of exposure. But rather than celebrating our uniqueness, we publish the same things everybody else does: selfies, food porn, and bullet journal snapshots. The one benefit to seeing other people’s stories is the reinforcement of FOMO (fear of missing out). The unlived life taunts one…

-

Taste the rainbow, on loop

There it was, crushing the human will. It was the antithesis to my Kindle Jenner, a screen of sanctity for focus and learning. The lite brite is an attention thief. Like a fresh bag of Skittles, it begs you to consume your favorite colors first. The rainbow hue of Instagram may be the shiniest of…

-

Four to one

The goal is to be good at more than one thing. Everyone should be versatile. But sometimes it is better to narrow yourself to expand. Instead of doing everything, you focus on doing one thing well. And the rest gets better as a result. Take social networking for example. It’s a misperception that one has…